While debate rages on in other corners of the web about what kinds of Gods we do or don’t believe in, I have been thinking about the way that we worship whatever/whomever we hold dear, sacred, and holy. I decided a series of posts that tackle this question from a deeply personal point of view would be useful to me, and perhaps to a few readers as well. I have also been thinking about shadows, storytelling, and ceremonies-so it seemed natural that I would start there.

In San Antonio summers shadows are important-for they are where we find darkness, a place to be hidden, and most essentially of all, coolness. As David Abram points out in his beautiful work Becoming Animal, night is the greatest shadow of them all and its during the night that stories we were once told, not read, but spoken, sung out, beaten on the hide of a drum, or danced in the light of the moon. Stories were told around campfires, sweat lodges, in the desert under the stars, and in the trees amid the branches and bracken. The more I walk into the realm of story the more I find it essential for an earth-based spiritual practice.

The first competition I ever engaged in was a storytelling competition. Because I live in a state that values excellence, swagger, and boldness (they often do work together), anything and everything can be made into a competitive event. Storytelling competition went like this: a story was selected, memorized and then, before a panel of judges, retold with dramatic interpretation and (one hoped) flair. I was in second grade when I started competing in storytelling, about seven years old.

Now with a child of my own the art of storytelling reaches out her withered, oft ignored, hand to hold mine-taking me down steps covered with moss and dust into a realm that knows something of both medicine and magic. We do not have a tv at my house. Instead, we have a baby grand piano (antique and well used) front and center in our living area-and while we do have electric lights and all the other modern conveniences that go along with them-both my husband and I appreciate natural darkness. We welcome the late falling of shadowy night as does our little one. It is at this time that I feel story’s hand reach for mine with the most insistence, at this time that a tale must be told and in our family I am usually the one to do it.

I have to admit that storytelling feels awkward at first. Incredibly well read, I find myself reaching back and dismissing the many philosophical treatises I have held in my mind, sacred texts, and long novels tend to go out as well. I look for the faerie and folk tales that I grew up with as a young girl-this is the straw I need to turn to gold. With no script to memorize or work off of, I am as fascinated as my listeners by the embellishments I add-Goldilocks was born in the spring as the snow melted down the mountains forming the rive that three bears desiring honey might follow one fateful Summer’s day-and I never know what twists and turns the tale will follow. Thought I do know the general direction we are headed in-I can tell you whether the skeleton belongs to a cat or a bear but the color, texture, and scent of the fur is where magic comes into play. At the beginning of telling a story my voice is stilted and cracking-tripping here and there as I try to gain a sense and nose for the terrain I am trotting over. But midway through the wind courses through our hair and we are all in, the story must be told until it is finished.

This ties to magic not only because storytelling is one of the oldest magics-perhaps the first Sacred Art, but because story is medicine and it has the power to transform-it is an old and ancient alchemy. It ties to my specific magical practice because part of my work is oracular in nature-meaning that I perform divination for people-and these sessions always begin with a prayer-for seeking a blessing is wise before any great endeavor-followed by a variation on the theme of “so tell me your story…”

Native American writer Linda Hogan describes this process when she seeks out the help of a wise man: “After eating and sitting, it is time for me to talk to him, to tell him why we have come here. I have brought him tobacco and he nods and listens as I tell him about the help we need. I know this telling is the first part of the ceremony, my part in it. It is story, really, that finds its way into language, and story is at the very crux of healing, at the heart of every ceremony and ritual in the older America.” —Linda Hogan, All My Relations

Indeed. When we orally tell stories we become aware of ourselves and our place-not in a clever, sophisticated, or abstract manner but in a specific, concrete, and grounded manner. Volume, tone, and word choice are factors the storyteller weighs and measures in the telling of our tales. This specificity of place and our way of being in a particular place is for me what earth-based spirituality is centered around. Telling stories with tongue, teeth, hand, --eye, hand, foot, and body is nothing less than devoted worship.

--

Featured Image (The Story of the Three Bears): Arthur Rackham: Steel, Flora Annie. English Fairy Tales. Arthur Rackham, illustrator. New York: Macmillan Company, 1918.

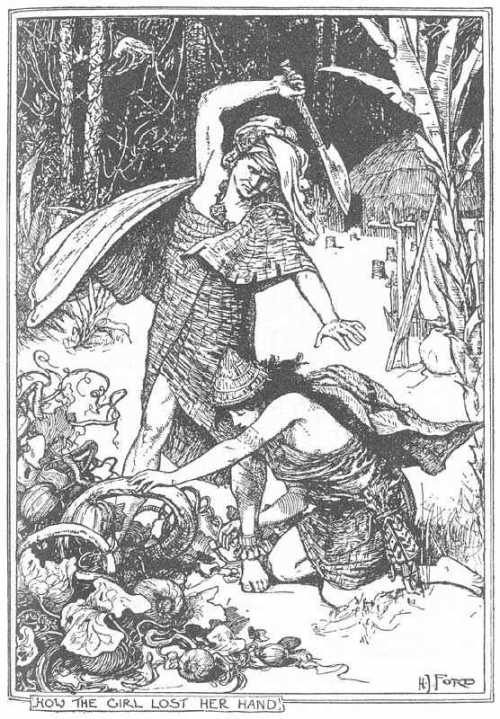

Second Image: artist (The Handless Maiden): H.J Ford From the book: Lang, Andrew, ed. The Lilac Fairy Book. New York: Dover, 1968. (Original published 1910.)

Third Image (Thumbelina): Andersen, Hans Christian. Stories for the Household. H. W. Dulcken, translator. A. W. Bayes, illustrator. London: George Routledge & Sons, 1889.

Linda Hogan's excellent essay "All My Relations" can be found in her book Dwellings.